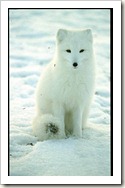

I guess that Arctic foxes had never encountered humans before because they would tamely approach us and dart around our feet seemingly unaware of the threat that people could impose. Their only predators were polar bears. In fact, I saw one bear chasing a fox over the path to the site behind me. Unaware that these beautiful but fearsome creatures could run so fast, I was duly impressed and, luckily for the fox, he outran the bear. This resulted in mixed feelings as we all knew that none of us could even hope to outrun these snorting white locomotives and we were next on the menu. We were all very respectful if not fearful of these animals. Having experienced several encounters with bears, I am now glad to view them in enclosures rather than face to face with no protection.

I guess that Arctic foxes had never encountered humans before because they would tamely approach us and dart around our feet seemingly unaware of the threat that people could impose. Their only predators were polar bears. In fact, I saw one bear chasing a fox over the path to the site behind me. Unaware that these beautiful but fearsome creatures could run so fast, I was duly impressed and, luckily for the fox, he outran the bear. This resulted in mixed feelings as we all knew that none of us could even hope to outrun these snorting white locomotives and we were next on the menu. We were all very respectful if not fearful of these animals. Having experienced several encounters with bears, I am now glad to view them in enclosures rather than face to face with no protection. One night, I had gone over to the “auditorium” to see the nightly movie (I remember that it was Sugarland Express with Goldie Hawn). As I trundled through the snow banks back to the quarters, the strangest sense of horror and foreboding overcame me and the hair on the back of my neck bristled and my heart raced. Not even daring to glance behind (wearing an arctic parka that would necessitate turning about face) I hurried as fast as I could to the barracks and rushed through the door into the vestibule a.k.a. “cold air lock” and, with a sigh of relief, slammed the door behind me. The first thing that caught my eye was a poster warning about the dangers of polar bears near or in the camp. The next morning we found polar bear tracks over the route that I had taken and they were huge – larger than my winter flying boots - sending a further chill down my spine.

One night, I had gone over to the “auditorium” to see the nightly movie (I remember that it was Sugarland Express with Goldie Hawn). As I trundled through the snow banks back to the quarters, the strangest sense of horror and foreboding overcame me and the hair on the back of my neck bristled and my heart raced. Not even daring to glance behind (wearing an arctic parka that would necessitate turning about face) I hurried as fast as I could to the barracks and rushed through the door into the vestibule a.k.a. “cold air lock” and, with a sigh of relief, slammed the door behind me. The first thing that caught my eye was a poster warning about the dangers of polar bears near or in the camp. The next morning we found polar bear tracks over the route that I had taken and they were huge – larger than my winter flying boots - sending a further chill down my spine. Now, back to the ice. Because of the dangerous condition of the ice, we roped together in fours with a tether to winches on the sturdier pack ice. The two divers who accompanied us donned their dry suits and, being roped together, demarcated areas using yellow ropes on the debris field where it was probably safe enough for one, two or four investigators. Then we set out to recover the victims, some of whom were on the surface of the ice, some frozen in the ice and the remainder under the ice in up to 110 feet, about 30 meters, of water which, by the way, had a temperature below zero Celsius due to the salt concentration.

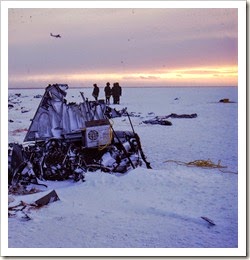

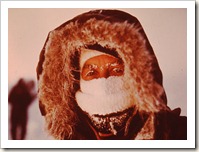

Now, back to the ice. Because of the dangerous condition of the ice, we roped together in fours with a tether to winches on the sturdier pack ice. The two divers who accompanied us donned their dry suits and, being roped together, demarcated areas using yellow ropes on the debris field where it was probably safe enough for one, two or four investigators. Then we set out to recover the victims, some of whom were on the surface of the ice, some frozen in the ice and the remainder under the ice in up to 110 feet, about 30 meters, of water which, by the way, had a temperature below zero Celsius due to the salt concentration.The wind was howling at over 50 knots which drove the equivalent temperature to about minus 100 degrees Fahrenheit and made it difficult to even stand. We had been issued chocolate pieces to chew on to keep our “furnaces” going as we intended to stay on the site for over 10 hours. The chocolate, which I kept in my parka’s pocket, was as hard as a rock! Since we were dressed in many thick layers of clothing requiring the release of as many zippers, answering the call of nature was a major undertaking and mightily uncomfortable as well as potentially gender altering, so we kept ourselves in a state of relative dehydration.

I stayed with the identification team, labelling, photographing and recovering the bodies on the surface of the ice. Normally we would pound in a metal stake where the bodies were found and affix a tag to the stake with an identical numbered tag to the victim for further mapping. This posed a real unforeseen problem as the wires on the tags fractured like strands of glass due to the extreme cold. We tried to use tape but it was so frozen that it would not stick. Therefore we were forced to resort to using plain ordinary string which necessitated removing our mitts in order to tie the knots resulting in frostbitten fingers. We would vacate the location while a second team came over to remove the victims on a toboggan as we could not chance having more than four plus the body at one time on the broken ice. Hence the process of recovering victims on the surface consumed more than 10 hours.

In the meantime the technical, structures and engineering investigators were mapping and photographing the overall site. There was a fair amount of wreckage on the surface, including one of the engines and other smaller debris, the “splash pattern”in the general direction of the runway and indicating a relatively low angle impact, known as CFIT (Controlled Flight Into Terrain) as defined by international protocol. It was immediately obvious that much of the debris was on the bottom of the sea and that underwater exploration would be necessary.

In the meantime the technical, structures and engineering investigators were mapping and photographing the overall site. There was a fair amount of wreckage on the surface, including one of the engines and other smaller debris, the “splash pattern”in the general direction of the runway and indicating a relatively low angle impact, known as CFIT (Controlled Flight Into Terrain) as defined by international protocol. It was immediately obvious that much of the debris was on the bottom of the sea and that underwater exploration would be necessary.We all headed back to the camp to warm up and have a hot meal. The food in these camps is of very high quality and full of calories to help personnel cope with the extreme environment.

At our evening meeting we expressed many concerns related to the underwater exploration and the safety of the team members:

1. We should have some kind of shelter. The oil company engineers supplied canvas and metal frame Quonset huts that would be relatively lightweight.

2. An expert in arctic sea ice pointed out that the ice was cracked between the accident site and the shore and that a wind shift could drive the site off to sea with the team members as unfortunate and unwilling passengers. Therefore, row boats would be placed on the ice near the cracks. They were, but we discovered a couple of days later that there were no oars in the boats!

3. Since the water was up to 110 feet deep, there was a risk of decompression sickness. Therefore a portable diving chamber was flown up from the south.

4. Because the water temperature was below freezing due to the salt content, traditional SCUBA gear would not suffice as water in the breath would freeze in the regulators. The divers were part of a Vancouver company that had invented “Rat Hats” with an air line and communication cables that would be connected to a compressor and physiological monitoring equipment on the surface. The divers also had a traditional diving suit as used by the navies and commercial divers of the world.

5. We needed the very best underwater specialist who was experienced in mapping and retrieving debris. An American who had supervised clearing out the Suez Canal after the 1956 conflict in the Middle East was retained and he would arrive in a couple of days.

6. It would be necessary to perform a survey of the sea bottom so that the underwater time of the divers could be optimized. This would be accomplished, under the direction of the expert, by lowering cameras through the ice at intervals along the crash path so that important items of wreckage could be located.

Exhausted, we all headed for the barracks to log some sack time.

Next time: Death in the Arctic - Back on the ice.

“On a Christmas Day we were mushing our way over the Dawson trail.

“On a Christmas Day we were mushing our way over the Dawson trail.Talk of the cold! through the parka’s fold it stabbed like a driven nail.

If our eyes we’d close then the lashes froze till sometimes we couldn’t see.

It wasn’t much fun, but the only one to whimper was Sam McGee.”

Robert Service: The Cremation of Sam McGee

When I read this I realize how tough job this must have been. Not only physically, but also mentally. Identify people from wreckage sites must be among the toughest work a man can have.

ReplyDeleteI wonder how you could prevent the Polar bears and Arctic Foxes from having their treat at the corpses laying around at the site, or was that an impossible task?

I know from plain crashes in Svalbard and other arctic places were Norwegian rescue groups have worked that this could bee a big problem. Particularly in the dark and cold of the Arctic winter.