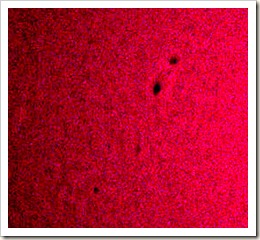

I haven’t written for a couple of weeks. I just turned 70 on the thirteenth of February (I was born on a Friday the Thirteenth!) and, aside from being quite busy, had a bit of writer’s block perhaps due to disbelief! (Also, the nightmares came back.) This past week has been quite nice here in Ottawa, though we had quite a bit of snow on Friday. On Tuesday, I was able to take some solar photos – here is a photo of sunspots – I processed the RAW images in Picasa. The sun was quite active this week with large flares and numerous sun spots so I enjoyed two afternoons of observing.

Back on the Ice

I haven’t written for a couple of weeks. I just turned 70 on the thirteenth of February (I was born on a Friday the Thirteenth!) and, aside from being quite busy, had a bit of writer’s block perhaps due to disbelief! (Also, the nightmares came back.) This past week has been quite nice here in Ottawa, though we had quite a bit of snow on Friday. On Tuesday, I was able to take some solar photos – here is a photo of sunspots – I processed the RAW images in Picasa. The sun was quite active this week with large flares and numerous sun spots so I enjoyed two afternoons of observing.

Back on the Ice

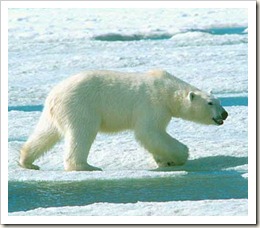

Well, things proceeded rapidly in the investigation of the L-188 crash. The underwater recovery expert arrived and the weather moderated somewhat so we were not so desperately cold. However, it was cold enough that the ice thickened up and became safer, allowing more of us on the ice at once. One thing that I would like to clarify and that is none of the victims were touched by polar bears. There was always a “hunter” guarding the site when we were not present. In fact this resulted in a somewhat humorous event though it could have resulted in serious injury or worse: On the afternoon of the third day, the hunter thought that he heard something behind the Quonset and, thinking that it was a bear, he blew the back wall out with his shotgun. Since this was the only shelter, the area behind the hut was the only place where a person could answer the call of nature. At the evening meeting, I persuaded the oil company to construct an

Well, things proceeded rapidly in the investigation of the L-188 crash. The underwater recovery expert arrived and the weather moderated somewhat so we were not so desperately cold. However, it was cold enough that the ice thickened up and became safer, allowing more of us on the ice at once. One thing that I would like to clarify and that is none of the victims were touched by polar bears. There was always a “hunter” guarding the site when we were not present. In fact this resulted in a somewhat humorous event though it could have resulted in serious injury or worse: On the afternoon of the third day, the hunter thought that he heard something behind the Quonset and, thinking that it was a bear, he blew the back wall out with his shotgun. Since this was the only shelter, the area behind the hut was the only place where a person could answer the call of nature. At the evening meeting, I persuaded the oil company to construct an  outhouse. In order to save weight, the engineers built it out of Styrofoam and 1/4 inch plywood and named it the “Skjenna Building!” This is the only time that I have had the honour (although perhaps dubious) of having a building named after me!

Another arrival from the sun drenched shores of California was Herman “Fish” Salmon, Lockheed’s famous and respected test pilot – a marvellous and hugely interesting character (check out his outstanding career on Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herman_Salmon .) He was representing the Lockheed corporation on this accident – it is the usual practice to have a company representative as a member of the team. In fact, I did represent Air Canada on the DC-9 accident in Cincinnati back in 1983 and was subsequently seconded to the NTSB. Well, Fish came directly from sunny climes

outhouse. In order to save weight, the engineers built it out of Styrofoam and 1/4 inch plywood and named it the “Skjenna Building!” This is the only time that I have had the honour (although perhaps dubious) of having a building named after me!

Another arrival from the sun drenched shores of California was Herman “Fish” Salmon, Lockheed’s famous and respected test pilot – a marvellous and hugely interesting character (check out his outstanding career on Wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herman_Salmon .) He was representing the Lockheed corporation on this accident – it is the usual practice to have a company representative as a member of the team. In fact, I did represent Air Canada on the DC-9 accident in Cincinnati back in 1983 and was subsequently seconded to the NTSB. Well, Fish came directly from sunny climes ![hsalmonsm[1] hsalmonsm[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiprWQr9JwElUbFr9r5CkmzFWEUT51qWf9JHxEAZeXn6oKLCtcCSswiHWx2SqrYU_abYWQ36nrslceL1YfefcEMFMynAQPE41AA29Bd8Qx6dr-cDSv1r-AI2XBNoSKv9lQfG_vmdVwgapo//?imgmax=800) and did not have any winter garments. We all pitched in and provided him with enough clothing so that he could venture out on the ice with us. One day I was standing with Fish enjoying a chat. He had his back to the crack in the ice that I mentioned before. Suddenly a seal broached in the water directly behind Fish. I didn’t know that a human could jump so high – I swear that I saw the soles of his boots when he reached apogee! Needless to say, anyone who observed this event dissolved in laughter. Sadly, Fish was killed in 1980 in the crash of a restored Super Constellation that he was delivering to Alaska . In 1994 he was inducted into the Aviation Walk of Fame.

Among the equipment that arrived was a hyperbaric chamber and a bottle of scotch. Although alcohol was forbidden on the base, I felt that some of the investigators, especially the ident team, could benefit from a wee dram so I had requested a container of hydroxylated ethane, preferably the kind manufactured in Scotland, and the Regional Aviation Medical Officer in Edmonton thankfully broke the code. Other equipment included underwater cameras, air pressurization pumps, physiological monitoring equipment and underwater communication equipment.

and did not have any winter garments. We all pitched in and provided him with enough clothing so that he could venture out on the ice with us. One day I was standing with Fish enjoying a chat. He had his back to the crack in the ice that I mentioned before. Suddenly a seal broached in the water directly behind Fish. I didn’t know that a human could jump so high – I swear that I saw the soles of his boots when he reached apogee! Needless to say, anyone who observed this event dissolved in laughter. Sadly, Fish was killed in 1980 in the crash of a restored Super Constellation that he was delivering to Alaska . In 1994 he was inducted into the Aviation Walk of Fame.

Among the equipment that arrived was a hyperbaric chamber and a bottle of scotch. Although alcohol was forbidden on the base, I felt that some of the investigators, especially the ident team, could benefit from a wee dram so I had requested a container of hydroxylated ethane, preferably the kind manufactured in Scotland, and the Regional Aviation Medical Officer in Edmonton thankfully broke the code. Other equipment included underwater cameras, air pressurization pumps, physiological monitoring equipment and underwater communication equipment.

The oil company engineers went to work and built a diving shack on the ice and cut a hole for the divers. As mentioned, the crew had done a pretty complete survey of the sea bottom so we could minimize the diver’s time in the water. Since we couldn’t bring all of the wreckage to the surface we relied on video and still pictures in order to examine engine settings and other pertinent details. This involved briefing the divers and then assisting them with the electronic communicators, the wires running along the oxygen hoses to microphones inside the helmets. Of course, the highest priority was recovery of the victims and this was accomplished within a few days – or 24 hour periods if you like, as daytime light was non-existent.

The oil company engineers went to work and built a diving shack on the ice and cut a hole for the divers. As mentioned, the crew had done a pretty complete survey of the sea bottom so we could minimize the diver’s time in the water. Since we couldn’t bring all of the wreckage to the surface we relied on video and still pictures in order to examine engine settings and other pertinent details. This involved briefing the divers and then assisting them with the electronic communicators, the wires running along the oxygen hoses to microphones inside the helmets. Of course, the highest priority was recovery of the victims and this was accomplished within a few days – or 24 hour periods if you like, as daytime light was non-existent.

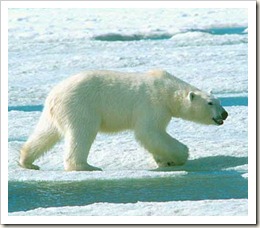

We did have one more close encounter with a polar bear. I was helping the Mounties recover a victim frozen in the ice. We were using chisels to chip away at the ice when I looked behind me and spotted three dark spots, the nose and eyes of a bear, approaching us. I told the sergeant and he glanced at the bear and continued chipping away. I started to become extremely anxious, but the Sarge would just look up and then chip away some more. At last, he picked up a shotgun and fired it into the air and, without even looking at the bear, continued to chip at the ice. Much to my relief, the bear ran away!

The Sarge was a legend in the North. He was a giant of a man with a very quiet and calm disposition. On one occasion, or so the legend goes, he was investigating the murder of an Eskimo by a fellow aboriginal. He did not let on that he spoke the language and, instead, hired an interpreter to translate. Unfortunately for the suspect he began to discuss the murder with the interpreter in native language whereupon the Sarge responded in the Eskimo language and slapped the handcuffs onto the hapless murderer!

The victims were flown to Edmonton. I contacted Dr. Neville Crowson, a dear friend and mentor, who was Canada’s leading expert in aviation crash pathology and he arrived in Edmonton to supervise the pathology. I was able to join him a few days later and assisted in the gathering of evidence.

One of the most pertinent findings was that the captain’s liver was grossly enlarged, about twice the normal size. Microscopic examination disclosed fatty infiltration with some inflammation. It turned out that he had a hobby farm and had been using carbon tetrachloride to clean his implements and tools. Carbon tet is very toxic to the liver and will interfere with liver function, for example the detoxification of amino acids. Since the crew had consumed a steak about an hour before the accident, it is most likely that high levels of amino acids had resulted in incapacitation. In fact the two surviving crew members indicated that the captain had descended to 300 feet about six miles from the beacon (the descent limit was 400 feet). As they approached the ice floes, he stated that they were above cloud and had to get below. He then pushed the nose of the aircraft down so violently that the crew experienced negative “G”. Both the first officer and flight engineer shouted out altitudes to the captain but he continued diving towards the ice. Finally, the first officer grabbed the control yoke and attempted to pull out, but it was too late. The aircraft hit the ice in about a seven degree nose down attitude. Much of the aircraft broke up and the cockpit slid about 900 feet and then sank. The two crewmen jumped out but the captain just stayed in his seat appearing to stare straight ahead and went down with the cockpit. These events indicated that he was impaired, not by alcohol, but by toxic levels of amino acids.

We did have one more close encounter with a polar bear. I was helping the Mounties recover a victim frozen in the ice. We were using chisels to chip away at the ice when I looked behind me and spotted three dark spots, the nose and eyes of a bear, approaching us. I told the sergeant and he glanced at the bear and continued chipping away. I started to become extremely anxious, but the Sarge would just look up and then chip away some more. At last, he picked up a shotgun and fired it into the air and, without even looking at the bear, continued to chip at the ice. Much to my relief, the bear ran away!

The Sarge was a legend in the North. He was a giant of a man with a very quiet and calm disposition. On one occasion, or so the legend goes, he was investigating the murder of an Eskimo by a fellow aboriginal. He did not let on that he spoke the language and, instead, hired an interpreter to translate. Unfortunately for the suspect he began to discuss the murder with the interpreter in native language whereupon the Sarge responded in the Eskimo language and slapped the handcuffs onto the hapless murderer!

The victims were flown to Edmonton. I contacted Dr. Neville Crowson, a dear friend and mentor, who was Canada’s leading expert in aviation crash pathology and he arrived in Edmonton to supervise the pathology. I was able to join him a few days later and assisted in the gathering of evidence.

One of the most pertinent findings was that the captain’s liver was grossly enlarged, about twice the normal size. Microscopic examination disclosed fatty infiltration with some inflammation. It turned out that he had a hobby farm and had been using carbon tetrachloride to clean his implements and tools. Carbon tet is very toxic to the liver and will interfere with liver function, for example the detoxification of amino acids. Since the crew had consumed a steak about an hour before the accident, it is most likely that high levels of amino acids had resulted in incapacitation. In fact the two surviving crew members indicated that the captain had descended to 300 feet about six miles from the beacon (the descent limit was 400 feet). As they approached the ice floes, he stated that they were above cloud and had to get below. He then pushed the nose of the aircraft down so violently that the crew experienced negative “G”. Both the first officer and flight engineer shouted out altitudes to the captain but he continued diving towards the ice. Finally, the first officer grabbed the control yoke and attempted to pull out, but it was too late. The aircraft hit the ice in about a seven degree nose down attitude. Much of the aircraft broke up and the cockpit slid about 900 feet and then sank. The two crewmen jumped out but the captain just stayed in his seat appearing to stare straight ahead and went down with the cockpit. These events indicated that he was impaired, not by alcohol, but by toxic levels of amino acids.

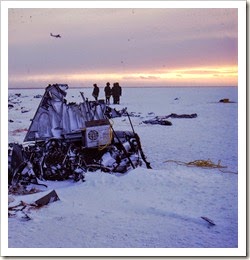

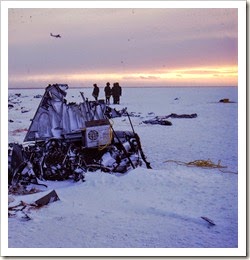

The only part of the aircraft brought up from the bottom was the cockpit as my very dramatic photo shows. This was done in order to examine instruments and switch settings although this is notoriously misleading. Unfortunately for the investigation, very little information was recovered from the flight data recorder and the cockpit voice recorder. A public inquiry was called and I, along with the other investigators worked on that for around two years and I spent considerable time on the witness stand, experience that would help me greatly in the future.

Man will occasionally stumble over the truth, but most of the time he will pick himself up and continue on.

The only part of the aircraft brought up from the bottom was the cockpit as my very dramatic photo shows. This was done in order to examine instruments and switch settings although this is notoriously misleading. Unfortunately for the investigation, very little information was recovered from the flight data recorder and the cockpit voice recorder. A public inquiry was called and I, along with the other investigators worked on that for around two years and I spent considerable time on the witness stand, experience that would help me greatly in the future.

Man will occasionally stumble over the truth, but most of the time he will pick himself up and continue on.

Winston Churchill

Today it is cold here in Ottawa, but only about minus 5 Celsius, a far cry from the weather in Rea Point in that fateful November of 1974* In fact, relatively balmy. The sun is shining brightly on the snow where, at that time of the year in the high Arctic, the sunshine consisted only of a faint rosy glow briefly seen on the horizon, making for eerie lighting over the accident site on the new ice though the aurora did often help us see. *(Actually, the accident occurred on October 30, but we were not on the ice until November 1).

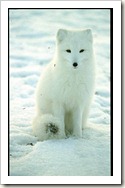

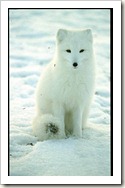

I guess that Arctic foxes had never encountered humans before because they would tamely approach us and dart around our feet seemingly unaware of the threat that people could impose. Their only predators were polar bears. In fact, I saw one bear chasing a fox over the path to the site behind me. Unaware that these beautiful but fearsome creatures could run so fast, I was duly impressed and, luckily for the fox, he outran the bear. This resulted in mixed feelings as we all knew that none of us could even hope to outrun these snorting white locomotives and we were next on the menu. We were all very respectful if not fearful of these animals. Having experienced several encounters with bears, I am now glad to view them in enclosures rather than face to face with no protection.

I guess that Arctic foxes had never encountered humans before because they would tamely approach us and dart around our feet seemingly unaware of the threat that people could impose. Their only predators were polar bears. In fact, I saw one bear chasing a fox over the path to the site behind me. Unaware that these beautiful but fearsome creatures could run so fast, I was duly impressed and, luckily for the fox, he outran the bear. This resulted in mixed feelings as we all knew that none of us could even hope to outrun these snorting white locomotives and we were next on the menu. We were all very respectful if not fearful of these animals. Having experienced several encounters with bears, I am now glad to view them in enclosures rather than face to face with no protection.

One night, I had gone over to the “auditorium” to see the nightly movie (I remember that it was Sugarland Express with Goldie Hawn). As I trundled through the snow banks back to the quarters, the strangest sense of horror and foreboding overcame me and the hair on the back of my neck bristled and my heart raced. Not even daring to glance behind (wearing an arctic parka that would necessitate turning about face) I hurried as fast as I could to the barracks and rushed through the door into the vestibule a.k.a. “cold air lock” and, with a sigh of relief, slammed the door behind me. The first thing that caught my eye was a poster warning about the dangers of polar bears near or in the camp. The next morning we found polar bear tracks over the route that I had taken and they were huge – larger than my winter flying boots - sending a further chill down my spine.

One night, I had gone over to the “auditorium” to see the nightly movie (I remember that it was Sugarland Express with Goldie Hawn). As I trundled through the snow banks back to the quarters, the strangest sense of horror and foreboding overcame me and the hair on the back of my neck bristled and my heart raced. Not even daring to glance behind (wearing an arctic parka that would necessitate turning about face) I hurried as fast as I could to the barracks and rushed through the door into the vestibule a.k.a. “cold air lock” and, with a sigh of relief, slammed the door behind me. The first thing that caught my eye was a poster warning about the dangers of polar bears near or in the camp. The next morning we found polar bear tracks over the route that I had taken and they were huge – larger than my winter flying boots - sending a further chill down my spine.

Now, back to the ice. Because of the dangerous condition of the ice, we roped together in fours with a tether to winches on the sturdier pack ice. The two divers who accompanied us donned their dry suits and, being roped together, demarcated areas using yellow ropes on the debris field where it was probably safe enough for one, two or four investigators. Then we set out to recover the victims, some of whom were on the surface of the ice, some frozen in the ice and the remainder under the ice in up to 110 feet, about 30 meters, of water which, by the way, had a temperature below zero Celsius due to the salt concentration.

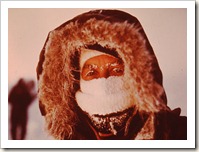

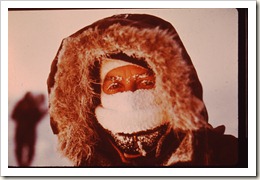

The wind was howling at over 50 knots which drove the equivalent temperature to about minus 100 degrees Fahrenheit and made it difficult to even stand. We had been issued chocolate pieces to chew on to keep our “furnaces” going as we intended to stay on the site for over 10 hours. The chocolate, which I kept in my parka’s pocket, was as hard as a rock! Since we were dressed in many thick layers of clothing requiring the release of as many zippers, answering the call of nature was a major undertaking and mightily uncomfortable as well as potentially gender altering, so we kept ourselves in a state of relative dehydration.

I stayed with the identification team, labelling, photographing and recovering the bodies on the surface of the ice. Normally we would pound in a metal stake where the bodies were found and affix a tag to the stake with an identical numbered tag to the victim for further mapping. This posed a real unforeseen problem as the wires on the tags fractured like strands of glass due to the extreme cold. We tried to use tape but it was so frozen that it would not stick. Therefore we were forced to resort to using plain ordinary string which necessitated removing our mitts in order to tie the knots resulting in frostbitten fingers. We would vacate the location while a second team came over to remove the victims on a toboggan as we could not chance having more than four plus the body at one time on the broken ice. Hence the process of recovering victims on the surface consumed more than 10 hours.

Now, back to the ice. Because of the dangerous condition of the ice, we roped together in fours with a tether to winches on the sturdier pack ice. The two divers who accompanied us donned their dry suits and, being roped together, demarcated areas using yellow ropes on the debris field where it was probably safe enough for one, two or four investigators. Then we set out to recover the victims, some of whom were on the surface of the ice, some frozen in the ice and the remainder under the ice in up to 110 feet, about 30 meters, of water which, by the way, had a temperature below zero Celsius due to the salt concentration.

The wind was howling at over 50 knots which drove the equivalent temperature to about minus 100 degrees Fahrenheit and made it difficult to even stand. We had been issued chocolate pieces to chew on to keep our “furnaces” going as we intended to stay on the site for over 10 hours. The chocolate, which I kept in my parka’s pocket, was as hard as a rock! Since we were dressed in many thick layers of clothing requiring the release of as many zippers, answering the call of nature was a major undertaking and mightily uncomfortable as well as potentially gender altering, so we kept ourselves in a state of relative dehydration.

I stayed with the identification team, labelling, photographing and recovering the bodies on the surface of the ice. Normally we would pound in a metal stake where the bodies were found and affix a tag to the stake with an identical numbered tag to the victim for further mapping. This posed a real unforeseen problem as the wires on the tags fractured like strands of glass due to the extreme cold. We tried to use tape but it was so frozen that it would not stick. Therefore we were forced to resort to using plain ordinary string which necessitated removing our mitts in order to tie the knots resulting in frostbitten fingers. We would vacate the location while a second team came over to remove the victims on a toboggan as we could not chance having more than four plus the body at one time on the broken ice. Hence the process of recovering victims on the surface consumed more than 10 hours.

In the meantime the technical, structures and engineering investigators were mapping and photographing the overall site. There was a fair amount of wreckage on the surface, including one of the engines and other smaller debris, the “splash pattern”in the general direction of the runway and indicating a relatively low angle impact, known as CFIT (Controlled Flight Into Terrain) as defined by international protocol. It was immediately obvious that much of the debris was on the bottom of the sea and that underwater exploration would be necessary.

We all headed back to the camp to warm up and have a hot meal. The food in these camps is of very high quality and full of calories to help personnel cope with the extreme environment.

At our evening meeting we expressed many concerns related to the underwater exploration and the safety of the team members:

1. We should have some kind of shelter. The oil company engineers supplied canvas and metal frame Quonset huts that would be relatively lightweight.

2. An expert in arctic sea ice pointed out that the ice was cracked between the accident site and the shore and that a wind shift could drive the site off to sea with the team members as unfortunate and unwilling passengers. Therefore, row boats would be placed on the ice near the cracks. They were, but we discovered a couple of days later that there were no oars in the boats!

3. Since the water was up to 110 feet deep, there was a risk of decompression sickness. Therefore a portable diving chamber was flown up from the south.

4. Because the water temperature was below freezing due to the salt content, traditional SCUBA gear would not suffice as water in the breath would freeze in the regulators. The divers were part of a Vancouver company that had invented “Rat Hats” with an air line and communication cables that would be connected to a compressor and physiological monitoring equipment on the surface. The divers also had a traditional diving suit as used by the navies and commercial divers of the world.

5. We needed the very best underwater specialist who was experienced in mapping and retrieving debris. An American who had supervised clearing out the Suez Canal after the 1956 conflict in the Middle East was retained and he would arrive in a couple of days.

6. It would be necessary to perform a survey of the sea bottom so that the underwater time of the divers could be optimized. This would be accomplished, under the direction of the expert, by lowering cameras through the ice at intervals along the crash path so that important items of wreckage could be located.

Exhausted, we all headed for the barracks to log some sack time.

Next time: Death in the Arctic - Back on the ice.

In the meantime the technical, structures and engineering investigators were mapping and photographing the overall site. There was a fair amount of wreckage on the surface, including one of the engines and other smaller debris, the “splash pattern”in the general direction of the runway and indicating a relatively low angle impact, known as CFIT (Controlled Flight Into Terrain) as defined by international protocol. It was immediately obvious that much of the debris was on the bottom of the sea and that underwater exploration would be necessary.

We all headed back to the camp to warm up and have a hot meal. The food in these camps is of very high quality and full of calories to help personnel cope with the extreme environment.

At our evening meeting we expressed many concerns related to the underwater exploration and the safety of the team members:

1. We should have some kind of shelter. The oil company engineers supplied canvas and metal frame Quonset huts that would be relatively lightweight.

2. An expert in arctic sea ice pointed out that the ice was cracked between the accident site and the shore and that a wind shift could drive the site off to sea with the team members as unfortunate and unwilling passengers. Therefore, row boats would be placed on the ice near the cracks. They were, but we discovered a couple of days later that there were no oars in the boats!

3. Since the water was up to 110 feet deep, there was a risk of decompression sickness. Therefore a portable diving chamber was flown up from the south.

4. Because the water temperature was below freezing due to the salt content, traditional SCUBA gear would not suffice as water in the breath would freeze in the regulators. The divers were part of a Vancouver company that had invented “Rat Hats” with an air line and communication cables that would be connected to a compressor and physiological monitoring equipment on the surface. The divers also had a traditional diving suit as used by the navies and commercial divers of the world.

5. We needed the very best underwater specialist who was experienced in mapping and retrieving debris. An American who had supervised clearing out the Suez Canal after the 1956 conflict in the Middle East was retained and he would arrive in a couple of days.

6. It would be necessary to perform a survey of the sea bottom so that the underwater time of the divers could be optimized. This would be accomplished, under the direction of the expert, by lowering cameras through the ice at intervals along the crash path so that important items of wreckage could be located.

Exhausted, we all headed for the barracks to log some sack time.

Next time: Death in the Arctic - Back on the ice.

“On a Christmas Day we were mushing our way over the Dawson trail.

Talk of the cold! through the parka’s fold it stabbed like a driven nail.

If our eyes we’d close then the lashes froze till sometimes we couldn’t see.

It wasn’t much fun, but the only one to whimper was Sam McGee.”

Robert Service: The Cremation of Sam McGee

“On a Christmas Day we were mushing our way over the Dawson trail.

Talk of the cold! through the parka’s fold it stabbed like a driven nail.

If our eyes we’d close then the lashes froze till sometimes we couldn’t see.

It wasn’t much fun, but the only one to whimper was Sam McGee.”

Robert Service: The Cremation of Sam McGee

I should warn you – I am jumping ahead many years as I have had a case of writer’s block lately and also I’ll tell you that what is about to be written is not altogether pleasant though you may find it interesting. I have been undergoing treatment for pre-malignant skin tumours on my face for the past month. The medication, 5-fluorouracil, is a very powerful cancer agent; one of the side effects can be feeling unwell which results in lack of motivation to do very much, including writing. However, the treatment is working very well as my face has been stripped of much of the epidermis (outer layer of the skin) - this is quite uncomfortable and interferes with mundane activities such as sleeping or consuming spicy foods. This condition arises from many years of sun exposure, for example 20 years of sailing, thousands of kilometers of riding motorcycles not to mention the years spent growing up on the prairie with inadequate skin protection. So please encourage everyone to use sunscreen, wear a hat, etc.

So here we go, back to the future as they say. I’ll tell you later about how I arrived at this place in my professional career and also regale you with further stories from the prairies.

November 1974, Dear diary,

The phone rang at about 0400 this morning. To an accident investigator, the telephone is about as welcome as a cobra because most of the time when it rings he will be away from home and his family for days or even months. It is difficult to describe one’s feelings as you approach the dreaded thing. There is a mixture of dread, anxiety and a sinking feeling in the pit of the stomach, almost a feeling of sickness. With much trepidation and with shaking hands I answered.

The sleepy sounding voice on the other end stated “a Lockheed L188 Electra has gone down in the high Arctic and the news that we have is that there are at least 32 fatalities. Be at the airport in two hours prepared to spend a few weeks away. We will take a commercial flight to Calgary and the oil company that owned the Electra will fly us up north on its sister ship. We have arranged for your tickets.”

So I hurriedly threw a few things in my kit – it was always nearly ready since I was a member of the “Go Team” - and rushed to the airport to meet up with the other investigators. I was dressed in my heavy cold weather gear as it was, after all, winter and the high Arctic is notorious for being extremely cold and inhospitable. As we winged our way from Winnipeg to Calgary we discussed the case on hand and began to formulate our approach.

Upon arriving in Calgary, we were briefed by the oil company management and safety personnel. According to them the aircraft had departed Calgary, landing first of all in Edmonton to pick up other oil company employees, and then heading to Rae Point which was way up north, above the range of normal maps and was actually north of the north magnetic pole! On approach into Rea Point, contact had been lost with the pilots and so, some time later, a Twin Otter belonging to the RCMP took off to have a look. The crew immediately spotted flames about 4 km. from the end of the runway and, having confirmed that it was an aircraft wreckage, rescuers were dispatched to the scene.

What they found was a carnage: There were aircraft parts scattered over the ice and only two survivors – the First Officer and the Flight Engineer. The First Officer was not badly injured but the Flight Engineer had frostbitten hands which he later had to have amputated. The Electra had gone down on new sea ice in line with the runway. Electra’s were one of the last of the high performance turboprop aircraft and were powered by four engines. The wings are quite stubby

I should warn you – I am jumping ahead many years as I have had a case of writer’s block lately and also I’ll tell you that what is about to be written is not altogether pleasant though you may find it interesting. I have been undergoing treatment for pre-malignant skin tumours on my face for the past month. The medication, 5-fluorouracil, is a very powerful cancer agent; one of the side effects can be feeling unwell which results in lack of motivation to do very much, including writing. However, the treatment is working very well as my face has been stripped of much of the epidermis (outer layer of the skin) - this is quite uncomfortable and interferes with mundane activities such as sleeping or consuming spicy foods. This condition arises from many years of sun exposure, for example 20 years of sailing, thousands of kilometers of riding motorcycles not to mention the years spent growing up on the prairie with inadequate skin protection. So please encourage everyone to use sunscreen, wear a hat, etc.

So here we go, back to the future as they say. I’ll tell you later about how I arrived at this place in my professional career and also regale you with further stories from the prairies.

November 1974, Dear diary,

The phone rang at about 0400 this morning. To an accident investigator, the telephone is about as welcome as a cobra because most of the time when it rings he will be away from home and his family for days or even months. It is difficult to describe one’s feelings as you approach the dreaded thing. There is a mixture of dread, anxiety and a sinking feeling in the pit of the stomach, almost a feeling of sickness. With much trepidation and with shaking hands I answered.

The sleepy sounding voice on the other end stated “a Lockheed L188 Electra has gone down in the high Arctic and the news that we have is that there are at least 32 fatalities. Be at the airport in two hours prepared to spend a few weeks away. We will take a commercial flight to Calgary and the oil company that owned the Electra will fly us up north on its sister ship. We have arranged for your tickets.”

So I hurriedly threw a few things in my kit – it was always nearly ready since I was a member of the “Go Team” - and rushed to the airport to meet up with the other investigators. I was dressed in my heavy cold weather gear as it was, after all, winter and the high Arctic is notorious for being extremely cold and inhospitable. As we winged our way from Winnipeg to Calgary we discussed the case on hand and began to formulate our approach.

Upon arriving in Calgary, we were briefed by the oil company management and safety personnel. According to them the aircraft had departed Calgary, landing first of all in Edmonton to pick up other oil company employees, and then heading to Rae Point which was way up north, above the range of normal maps and was actually north of the north magnetic pole! On approach into Rea Point, contact had been lost with the pilots and so, some time later, a Twin Otter belonging to the RCMP took off to have a look. The crew immediately spotted flames about 4 km. from the end of the runway and, having confirmed that it was an aircraft wreckage, rescuers were dispatched to the scene.

What they found was a carnage: There were aircraft parts scattered over the ice and only two survivors – the First Officer and the Flight Engineer. The First Officer was not badly injured but the Flight Engineer had frostbitten hands which he later had to have amputated. The Electra had gone down on new sea ice in line with the runway. Electra’s were one of the last of the high performance turboprop aircraft and were powered by four engines. The wings are quite stubby  resulting in quite a high wing loading and hence the approach speeds are about as fast as a pure jet aircraft. These machines were used extensively in the north after the airlines got rid of them as they converted to pure jet aircraft like Boeings and Douglas airliners.

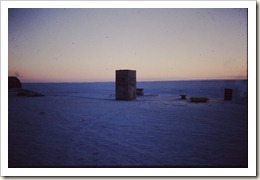

Rea Point was an oil exploration camp, searching for undersea oil in the high arctic. Since it was inaccessible by land all of the buildings and equipment had to be flown in by Hercules aircraft and were then bolted together to form barracks, cookhouses, storage facilities, offices and meeting rooms. During the winter, their large-tired machines were dispatched over the ice to look for potential drilling sites. When they found a likely spot, they would flood the surface of the ice in order to fashion a runway strong enough for the Hercules aircraft who would fly the drilling equipment to the site. As summer approached the wells would be capped until the next season. Since magnetic compasses were useless there, all navigation had to be done using radio beacons and sun compasses. Like almost all northern camps gambling and alcohol were prohibited. In fact one of the oil company employees had his life saved by a bottle of whiskey when a search of his luggage was performed. He was kicked off the flight in Edmonton – I wonder if he still has that bottle!

After several hours of flying we approached Rea Point. I rode in the jump seat as the head of the human factors team so I could observe the approach to see if I could pick up any clues of what may possibly have happened. The survivors had already been airlifted to Edmonton so we did not have an opportunity to interview them right away, which is the usual case. Accompanying us on the trip were six RCMP officers, some company management, two divers and and an insurance broker. We spent a couple of hours discussing the event and then grabbed a couple of hours of shuteye. At first light (there is not very much light at that time of the year) we gathered for a further briefing.

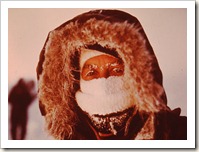

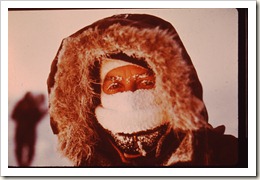

Everyone was anxious to head out onto the ice, but due to concern about the condition of the ice we organized into teams of four who would be roped together and tethered by a long rope to safer ice. Fresh sea ice is, after all, not very strong and also the ice had been broken up by the crash. In addition, it was extremely cold – the equivalent temperature (like wind chill) was minus 103 degrees Fahrenheit. Cold weather gear was an absolute requirement. Most of us had some part of our bodies frostbitten – for me it was a couple of fingers as I had to remove my heavy winter mitts in order to operate my camera. These photos were taken by me on my Pentax Spotmatic. I kept the camera warm by tucking it in behind my neck in the parka and only pulled it out when I knew that a photo was warranted.

resulting in quite a high wing loading and hence the approach speeds are about as fast as a pure jet aircraft. These machines were used extensively in the north after the airlines got rid of them as they converted to pure jet aircraft like Boeings and Douglas airliners.

Rea Point was an oil exploration camp, searching for undersea oil in the high arctic. Since it was inaccessible by land all of the buildings and equipment had to be flown in by Hercules aircraft and were then bolted together to form barracks, cookhouses, storage facilities, offices and meeting rooms. During the winter, their large-tired machines were dispatched over the ice to look for potential drilling sites. When they found a likely spot, they would flood the surface of the ice in order to fashion a runway strong enough for the Hercules aircraft who would fly the drilling equipment to the site. As summer approached the wells would be capped until the next season. Since magnetic compasses were useless there, all navigation had to be done using radio beacons and sun compasses. Like almost all northern camps gambling and alcohol were prohibited. In fact one of the oil company employees had his life saved by a bottle of whiskey when a search of his luggage was performed. He was kicked off the flight in Edmonton – I wonder if he still has that bottle!

After several hours of flying we approached Rea Point. I rode in the jump seat as the head of the human factors team so I could observe the approach to see if I could pick up any clues of what may possibly have happened. The survivors had already been airlifted to Edmonton so we did not have an opportunity to interview them right away, which is the usual case. Accompanying us on the trip were six RCMP officers, some company management, two divers and and an insurance broker. We spent a couple of hours discussing the event and then grabbed a couple of hours of shuteye. At first light (there is not very much light at that time of the year) we gathered for a further briefing.

Everyone was anxious to head out onto the ice, but due to concern about the condition of the ice we organized into teams of four who would be roped together and tethered by a long rope to safer ice. Fresh sea ice is, after all, not very strong and also the ice had been broken up by the crash. In addition, it was extremely cold – the equivalent temperature (like wind chill) was minus 103 degrees Fahrenheit. Cold weather gear was an absolute requirement. Most of us had some part of our bodies frostbitten – for me it was a couple of fingers as I had to remove my heavy winter mitts in order to operate my camera. These photos were taken by me on my Pentax Spotmatic. I kept the camera warm by tucking it in behind my neck in the parka and only pulled it out when I knew that a photo was warranted.

We all headed across the old ice, some of us in snowmobiles which were kept running 24/7 or else they wouldn’t start. My companion, the insurance adjuster, and I stopped at the edge of the piled up pack ice to view the scene of devastation. As we sat there, I detected a movement to the left of the snowmobile – it was an enormous polar bear and it stood right up attaining its maximum height – those things are huge! It was less than 20 feet away and I thought that we were goners for sure. I guess that the sound of our engine spooked it as, after looking at two potential meals for a few seconds, it ran away to our left towards my medical colleague, Dr. Roy Hewson who happened to be on foot. I fretted about Roy for a couple of minutes but the bear kept racing past him. These bears continued to be a bit of a nuisance as there were still bodies on the ice and the aircraft had been carrying ten thousand pounds of meat for human consumption in the camp. Polar bears are also man eaters and they will actually hunt humans for food. In fact while we were up there a cook in another camp had stepped outside of the cook house for a smoke and was killed and dragged off by a polar bear proving that smoking is injurious to one’s health. Since only northern aboriginals were allowed to kill them, we had an armed Eskimo accompanying us at all times. The oil company had also placed rifles and shotguns in the wreckage just in case – they hadn’t figured out that they would be unable to fire due to the cold!

My friend questioned me about dealing with polar bears. I told him that we should always walk together and if we saw a bear approaching run like crazy. He told me that he doubted that I could outrun one of these creatures, to which I replied “probably not, but I’m pretty sure that I can outrun you!”

Little did I know that I would be spending the next two years working on this case.

Next – Death in the Arctic – Part Two - Recovery and Discovery

We all headed across the old ice, some of us in snowmobiles which were kept running 24/7 or else they wouldn’t start. My companion, the insurance adjuster, and I stopped at the edge of the piled up pack ice to view the scene of devastation. As we sat there, I detected a movement to the left of the snowmobile – it was an enormous polar bear and it stood right up attaining its maximum height – those things are huge! It was less than 20 feet away and I thought that we were goners for sure. I guess that the sound of our engine spooked it as, after looking at two potential meals for a few seconds, it ran away to our left towards my medical colleague, Dr. Roy Hewson who happened to be on foot. I fretted about Roy for a couple of minutes but the bear kept racing past him. These bears continued to be a bit of a nuisance as there were still bodies on the ice and the aircraft had been carrying ten thousand pounds of meat for human consumption in the camp. Polar bears are also man eaters and they will actually hunt humans for food. In fact while we were up there a cook in another camp had stepped outside of the cook house for a smoke and was killed and dragged off by a polar bear proving that smoking is injurious to one’s health. Since only northern aboriginals were allowed to kill them, we had an armed Eskimo accompanying us at all times. The oil company had also placed rifles and shotguns in the wreckage just in case – they hadn’t figured out that they would be unable to fire due to the cold!

My friend questioned me about dealing with polar bears. I told him that we should always walk together and if we saw a bear approaching run like crazy. He told me that he doubted that I could outrun one of these creatures, to which I replied “probably not, but I’m pretty sure that I can outrun you!”

Little did I know that I would be spending the next two years working on this case.

Next – Death in the Arctic – Part Two - Recovery and Discovery

I haven’t written for a couple of weeks. I just turned 70 on the thirteenth of February (I was born on a Friday the Thirteenth!) and, aside from being quite busy, had a bit of writer’s block perhaps due to disbelief! (Also, the nightmares came back.) This past week has been quite nice here in Ottawa, though we had quite a bit of snow on Friday. On Tuesday, I was able to take some solar photos – here is a photo of sunspots – I processed the RAW images in Picasa. The sun was quite active this week with large flares and numerous sun spots so I enjoyed two afternoons of observing.

I haven’t written for a couple of weeks. I just turned 70 on the thirteenth of February (I was born on a Friday the Thirteenth!) and, aside from being quite busy, had a bit of writer’s block perhaps due to disbelief! (Also, the nightmares came back.) This past week has been quite nice here in Ottawa, though we had quite a bit of snow on Friday. On Tuesday, I was able to take some solar photos – here is a photo of sunspots – I processed the RAW images in Picasa. The sun was quite active this week with large flares and numerous sun spots so I enjoyed two afternoons of observing.

outhouse. In order to save weight, the engineers built it out of Styrofoam and 1/4 inch plywood and named it the “Skjenna Building!” This is the only time that I have had the honour (although perhaps dubious) of having a building named after me!

outhouse. In order to save weight, the engineers built it out of Styrofoam and 1/4 inch plywood and named it the “Skjenna Building!” This is the only time that I have had the honour (although perhaps dubious) of having a building named after me!![hsalmonsm[1] hsalmonsm[1]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEiprWQr9JwElUbFr9r5CkmzFWEUT51qWf9JHxEAZeXn6oKLCtcCSswiHWx2SqrYU_abYWQ36nrslceL1YfefcEMFMynAQPE41AA29Bd8Qx6dr-cDSv1r-AI2XBNoSKv9lQfG_vmdVwgapo//?imgmax=800) and did not have any winter garments. We all pitched in and provided him with enough clothing so that he could venture out on the ice with us. One day I was standing with Fish enjoying a chat. He had his back to the crack in the ice that I mentioned before. Suddenly a seal broached in the water directly behind Fish. I didn’t know that a human could jump so high – I swear that I saw the soles of his boots when he reached apogee! Needless to say, anyone who observed this event dissolved in laughter. Sadly, Fish was killed in 1980 in the crash of a restored Super Constellation that he was delivering to Alaska . In 1994 he was inducted into the Aviation Walk of Fame.

and did not have any winter garments. We all pitched in and provided him with enough clothing so that he could venture out on the ice with us. One day I was standing with Fish enjoying a chat. He had his back to the crack in the ice that I mentioned before. Suddenly a seal broached in the water directly behind Fish. I didn’t know that a human could jump so high – I swear that I saw the soles of his boots when he reached apogee! Needless to say, anyone who observed this event dissolved in laughter. Sadly, Fish was killed in 1980 in the crash of a restored Super Constellation that he was delivering to Alaska . In 1994 he was inducted into the Aviation Walk of Fame. The oil company engineers went to work and built a diving shack on the ice and cut a hole for the divers. As mentioned, the crew had done a pretty complete survey of the sea bottom so we could minimize the diver’s time in the water. Since we couldn’t bring all of the wreckage to the surface we relied on video and still pictures in order to examine engine settings and other pertinent details. This involved briefing the divers and then assisting them with the electronic communicators, the wires running along the oxygen hoses to microphones inside the helmets. Of course, the highest priority was recovery of the victims and this was accomplished within a few days – or 24 hour periods if you like, as daytime light was non-existent.

The oil company engineers went to work and built a diving shack on the ice and cut a hole for the divers. As mentioned, the crew had done a pretty complete survey of the sea bottom so we could minimize the diver’s time in the water. Since we couldn’t bring all of the wreckage to the surface we relied on video and still pictures in order to examine engine settings and other pertinent details. This involved briefing the divers and then assisting them with the electronic communicators, the wires running along the oxygen hoses to microphones inside the helmets. Of course, the highest priority was recovery of the victims and this was accomplished within a few days – or 24 hour periods if you like, as daytime light was non-existent. We did have one more close encounter with a polar bear. I was helping the Mounties recover a victim frozen in the ice. We were using chisels to chip away at the ice when I looked behind me and spotted three dark spots, the nose and eyes of a bear, approaching us. I told the sergeant and he glanced at the bear and continued chipping away. I started to become extremely anxious, but the Sarge would just look up and then chip away some more. At last, he picked up a shotgun and fired it into the air and, without even looking at the bear, continued to chip at the ice. Much to my relief, the bear ran away!

We did have one more close encounter with a polar bear. I was helping the Mounties recover a victim frozen in the ice. We were using chisels to chip away at the ice when I looked behind me and spotted three dark spots, the nose and eyes of a bear, approaching us. I told the sergeant and he glanced at the bear and continued chipping away. I started to become extremely anxious, but the Sarge would just look up and then chip away some more. At last, he picked up a shotgun and fired it into the air and, without even looking at the bear, continued to chip at the ice. Much to my relief, the bear ran away! The only part of the aircraft brought up from the bottom was the cockpit as my very dramatic photo shows. This was done in order to examine instruments and switch settings although this is notoriously misleading. Unfortunately for the investigation, very little information was recovered from the flight data recorder and the cockpit voice recorder. A public inquiry was called and I, along with the other investigators worked on that for around two years and I spent considerable time on the witness stand, experience that would help me greatly in the future.

The only part of the aircraft brought up from the bottom was the cockpit as my very dramatic photo shows. This was done in order to examine instruments and switch settings although this is notoriously misleading. Unfortunately for the investigation, very little information was recovered from the flight data recorder and the cockpit voice recorder. A public inquiry was called and I, along with the other investigators worked on that for around two years and I spent considerable time on the witness stand, experience that would help me greatly in the future.